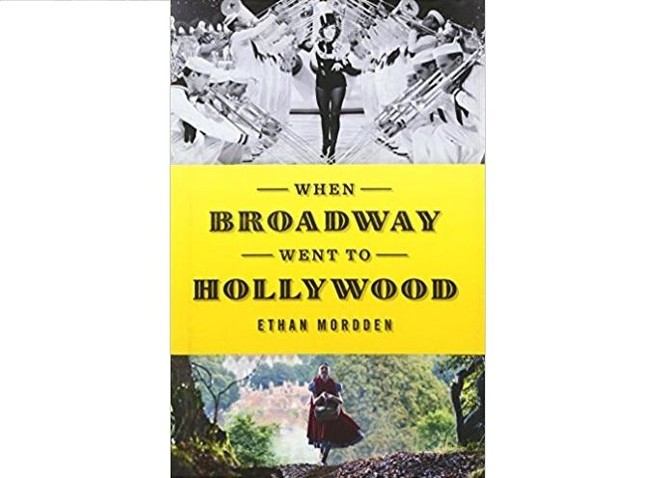

It takes an expert to measure Broadway’s influence on Hollywood and vice versa, but American author Ethan Mordden has the knowledge and inimitable wit to do so. In “When Broadway Went to Hollywood,” Mordden takes us behind the scenes of the great Hollywood musicals we have loved for years and discusses the impact of Broadway musicals on the movie industry.

Broadway is the theatrical district in New York City that is well-known for being the American capital of musical theater and in this book, readers gain insight into how the influx of immigrants shaped this thriving creative hub.

During the 19th century, German and Scandinavian immigrants who entered the US moved to the Midwest where a large portion became farmers. The Irish, Italian and Jewish newcomers preferred to settle in the cities of the Northeast and many moved into the entertainment business, according to the book. In the 1920s, black talent also joined in to create a multi-cultural melting pot.

It was “The Jazz Singer” that started it all. Made in 1927, it was the first movie to feature sound sequences. Originally, the lead role was given to actor George Jessel. But Jessel is said to have made demands and Warner Brothers replaced him with Al Jolson. Al Jolson could sing and had an “electrifying” presence on stage, he had the power and the talent to let “the vocals leap off the screen, take the audience into the future,” writes Mordden. Jonson sang the song “Blue Skies” and it was an immediate hit with audiences.

“This is the song that invented the Hollywood musical as the centerpiece of The Jazz Singer’s most effective sound sequence,” explains Mordden. Written by Irving Berlin, whose first songs date back to 1907, “Blue Skies” and its emotionally-charged scene was the highlight of the film. “Like him or not, he has the energy that set the Hollywood musical on the way to the rest of its life.”

Irving Berlin soon discovered that Hollywood could not offer creative freedom due to the constant interference of studio chiefs and producers. However, Berlin got lured back to Hollywood to work on “Top Hat,” which only features five of his songs.

George Gershwin and his brother Ira were also part of a limited number of Broadway professional songwriters working for Hollywood. Gershwin’s fate was sealed during a concert entitled “An Experiment in Modern Music.” Heavyweights in Manhattan attended this unique event to hear Gershwin’s latest opus, “A Rhapsody in Blue.” It was a triumph and it got Gershwin on the cover of Time magazine. As expected, he was soon in high demand in Hollywood.

Cole Porter is another famous songwriter, but unlike other Broadway talents, he loved Hollywood. During an interview with American journalist Dorothy Kilgallen, he said: “When I first came here they told me, ‘You’ll be so bored you’ll die, nobody talks about anything but pictures.’ After I was here a week, I discovered I didn’t want to talk about anything else myself.”

Porter’s collaboration with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) worked out well thanks to the company’s decision to pair him with composer-arrangers Herbert Stothart and Roger Edens. “Their imagination in putting a number together with full awareness of how the music affects the optics was elemental in the dominance of the MGM musical,” writes Mordden.

From 1940 to 1949, another golden age began due to MGM’s musicals such as “Meet me in St. Louis” and “The Pirate.” From 1950 to 1959, Broadway adaptations become more popular than ever, but the breakup of the studio system with its music departments meant that musicals were more expensive to produce. Between 1960 and 1975, Hollywood experienced a golden era with the production of great musicals such as “West Side Story,” “My Fair Lady” and “The Sound of Music.”

From 1976 to the present, Hollywood has flooded Broadway with stage versions of original Hollywood musicals such as “Gigi,” “Singin’ in the Rain” and “Footloose.” Hollywood also produced movie versions of famous Broadway shows, such as “Annie,” which was a hit on Broadway from 1977 to 1983. This should have been an easy production until John Huston was hired to direct the movie. The choreography in Annie involved lots of non-athletic acrobatics who lacked grace and beauty and some of the show’s best numbers were dropped. “It was an expensive mistake at the cost of something like a million dollars, and one of the reasons Annie did good business and still lost money,” Mordden wrote of the expensive movie-making process and the talented stars who came on board but whose suggestions were never used.

Fast forward to today and “La La Land,” a musical specially written for the silver screen, has been a resounding success. “Musicals are back,” writes Mordden. but had they ever disappeared? Can they disappear? With the crushing pressure of world events, we all need a place to escape to.

Book Review: How Broadway took Hollywood by storm

Book Review: How Broadway took Hollywood by storm

Book Review: ‘Keep the Memories, Lose the Stuff’

If you are someone who adopts a new year, new me mindset every Dec. 31, then Matt Paxton’s 2022 book “Keep the Memories, Lose the Stuff: Declutter, Downsize, and Move Forward with Your Life,” written with Jordan Michael Smith, is worth picking up.

In the process of reading it, I found myself filling four bags with items to donate.

Paxton’s approach is notably different from Marie Kondo’s once-ubiquitous Japanese tidying method, which asks readers to pile all their possessions into one part of the room, hold each item up and ask whether it sparks joy.

While Kondo’s philosophy sounds appealing on paper — thanking objects and dedicating an entire weekend to the process — it is not realistic for everyday life. Paxton’s method feels more practical and gentler.

Paxton knows the emotional terrain of clutter well. For more than 20 years he has helped people declutter and downsize. He was a featured cleaner on the reality show “Hoarders” and later hosted the Emmy-nominated “Legacy List with Matt Paxton” on PBS.

Through this work, Paxton gained insight into why people hold on to things and what makes letting go difficult even of what seemingly looks useless.

What works especially well is how personal the book feels from the outset.

He opens by explaining his anxiety-inducing decision to move to a different US state with his three children, and all of their stuff, to live with his new wife and all of her stuff.

Together, they would be raising seven children — very Brady Bunch style — but with slightly more practical life considerations.

He also talks about how he got into this line of work. When he was in his 20s, his father died and he had to help clear out his belongings. He found that process to be cathartic and special. And he was good at it.

Soon after, short on cash, he accepted a job from someone in his small, close-knit community to help organize her home — likely hired out of pity more than anything else.

That slow process of sifting through items and learning the stories behind each one — directly from the owner of those objects — sparked plenty of joy. He was hooked.

Throughout the book, Paxton makes the case for consistency. His advice is manageable. He encourages readers to dedicate just 10 minutes a day to decluttering to form a habit. We all can spare that.

Paxton also stresses the importance of communication.

Talk to your loved ones about what you want done with your belongings when you are no longer around, and just as importantly, listen to what they want done with theirs, he urges. He offers practical guidance on having these conversations with parents, partners and children.

One critique of this book is that Paxton dedicates a large portion to physical photographs. While this is relevant for many older readers, it may feel less urgent going forward, particularly for Gen Z and younger, whose clutter is more likely to be solely digital.

Ultimately, “Keep the Memories, Lose the Stuff” is less about getting rid of things than about making space; by speaking about objects, sharing their stories and allowing them — and each of us — to move on.