JAZRA, Syria: Since she fled her home near the militant stronghold of Raqqa in northern Syria more than a month ago, Warda Al-Jassem has been impatient to return — to water her vine.

Saving their grapes has become an obsession for the 50-year-old and her husband since fighting forced them to flee.

Their house is in Jazra, a western suburb of Raqqa, the Daesh group’s de facto Syrian capital from which a US-backed alliance of Arab and Kurdish fighters is battling to oust the militants.

Al-Jassem and her husband, who have taken refuge in the Al-Andalus area some 25 km north of Raqqa, could not stop worrying about their grapes.

Accompanied by neighbors, she headed home over the weekend for her first visit since Daesh was forced from the neighborhood in early June.

Due to a heart problem, her husband could not join her.

“Since we left here, the only thing he wanted was to know what had happened to the vine,” she said.

“Every day he’d say ‘The vine is thirsty, it has to be watered.’”

So “I came back to water it,” she said.

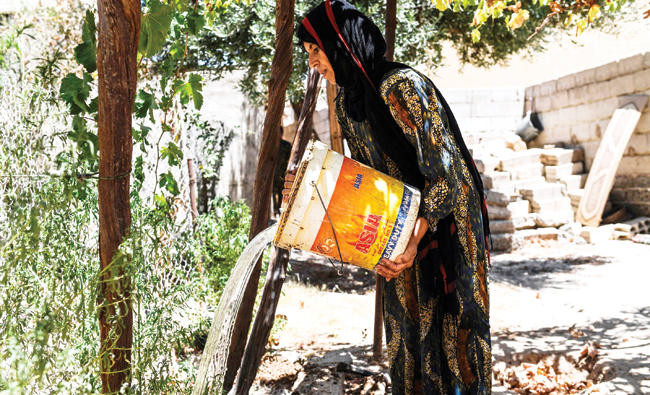

The blue-eyed woman, her head covered with a black embroidered veil, eyed a trellis hung with yellowed grapes and parched vine leaves.

“They were dying of thirst,” she said.

Much of the fruit had faded, but some grapes, still green, seemed to have survived the intense summer heat.

A determined look on her face, Al-Jassem turned over the earth with a shovel. Then, using a bucket, she poured water at the bottom of the trellis to try to save the rest of the vine.

Only then did she smile, her mission accomplished. She urged her friends to gather those grapes that were still edible.

Inside the house, she hastened to recover a few precious items: Bags of dried mint and other seasonings.

Before leaving again, she filled a plastic bottle with heating oil from a barrel on the patio.

A Syrian couple’s quest to save the grapes of Raqqa

A Syrian couple’s quest to save the grapes of Raqqa

These shy, scaly anteaters are the most trafficked mammals in the world

CAPE TOWN, South Africa: They are hunted for their unique scales, and the demand makes them the most trafficked mammal in the world.

Wildlife conservationists are again raising the plight of pangolins, the shy, scaly anteaters found in parts of Africa and Asia, on World Pangolin Day on Saturday.

Pangolins or pangolin products outstrip any other mammal when it comes to wildlife smuggling, with more than half a million pangolins seized in anti-trafficking operations between 2016 and 2024, according to a report last year by CITES, the global authority on the trading of endangered plant and animal species.

The World Wildlife Fund estimates that over a million pangolins were taken from the wild over the last decade, including those that were never intercepted.

Pangolins meat is a delicacy in places, but the driving force behind the illegal trade is their scales, which are made of keratin, the protein also found in human hair and fingernails. The scales are in high demand in China and other parts of Asia due to the unproven belief that they cure a range of ailments when made into traditional medicine.

There are eight pangolin species, four in Africa and four in Asia. All of them face a high, very high or extremely high risk of extinction.

While they’re sometimes known as scaly anteaters, pangolins are not related in any way to anteaters or armadillos.

They are unique in that they are the only mammals covered completely in keratin scales, which overlap and have sharp edges. They are the perfect defense mechanism, allowing a pangolin to roll up into an armored ball that even lions struggle to get to grip with, leaving the nocturnal ant and termite eaters with few natural predators.

But they have no real defense against human hunters. And in conservation terms, they don’t resonate in the way that elephants, rhinos or tigers do despite their fascinating intricacies — like their sticky insect-nabbing tongues being almost as long as their bodies.

While some reports indicate a downward trend in pangolin trafficking since the COVID-19 pandemic, they are still being poached at an alarming rate across parts of Africa, according to conservationists.

Nigeria is one of the global hot spots. There, Dr. Mark Ofua, a wildlife veterinarian and the West Africa representative for the Wild Africa conservation group, has rescued pangolins for more than a decade, which started with him scouring bushmeat markets for animals he could buy and save. He runs an animal rescue center and a pangolin orphanage in Lagos.

His mission is to raise awareness of pangolins in Nigeria through a wildlife show for kids and a tactic of convincing entertainers, musicians and other celebrities with millions of social media followers to be involved in conservation campaigns — or just be seen with a pangolin.

Nigeria is home to three of the four African pangolin species, but they are not well known among the country’s 240 million people.

Ofua’s drive for pangolin publicity stems from an encounter with a group of well-dressed young men while he was once transporting pangolins he had rescued in a cage. The men pointed at them and asked him what they were, Ofua said.

“Oh, those are baby dragons,” he joked. But it got him thinking.

“There is a dark side to that admission,” Ofua said. “If people do not even know what a pangolin looks like, how do you protect them?”