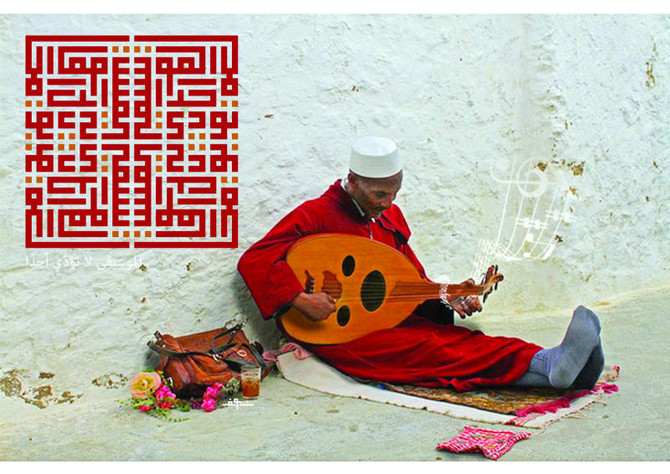

Within the Islamic culture the art of Khatt (calligraphy) is understood as the art of the pen and an expression of the sacred. It’s a practice that has been studied for ages. Since the development of the Arabic language, the progression of calligraphy became one of the major forms of artistic expression. It takes time and dedication to perfect the right script using tools only a serious artist would understand. It’s a form of expression, which is intertwined with oneself thus leading to great results. It’s not difficult to find artists practicing different types of Arabic calligraphy and excelling in them. It’s widely known that the art of Khatt was practiced since the early years after the birth of Islam as calligraphy was used to write the words of the Holy Qur’an.

Scripts were created to serve different purposes such as to write the words of the Qur’an, poetry, official paper work and royal decrees. It’s progressed throughout the years by even combining various aspects in architecture, different floras and using natural sources such as wood, feather and even rock at times. Some stood the sands of time as others died out. One of the more difficult types is Kufi. Yet one young Saudi has proved that it isn’t as difficult as it was once assumed. Youssef Yahya, a senior in the university studying architecture defied the difficulties and incorporated his field of education with his love for calligraphy.

His love for calligraphy started at a young age as he used to mimic his older brother, who was very skilled in calligraphy, but found it difficult to do so because he lacked the tools and support needed to develop the skill. Years later, after enrolling into the Department of Architecture at the Faculty of Environmental Design, this young man found the missing link between architectural geometric designs and Kufi calligraphy as they both refer back to grid modules and reference lines.

“Beginnings are always challenging. The first challenge laid in not finding sources and references to teach me the basics. My main source became the visual feeds of the pioneers of the Kufi art. I started studying and analyzing them and therefore concluded what I learnt throughout this research,” said Youssef. He believed that experience is the best inspiration and teacher.

Calligraphy is the soul of cultures and civilizations. Like anything in life, there are times where certain art is forgotten. However, today, there is a global interest in calligraphy and developing it in a way that serves countries, organization and youth alike. The relationship between the calligrapher and the script goes beyond the art piece canvas, it’s an unexplainable state of mind that the calligrapher and the calligraphy live in.

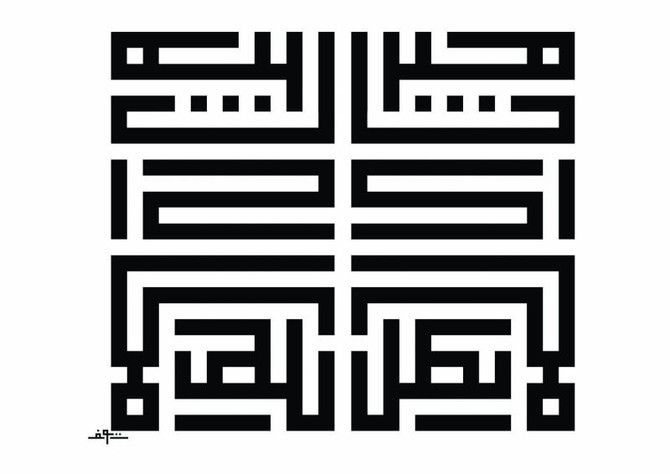

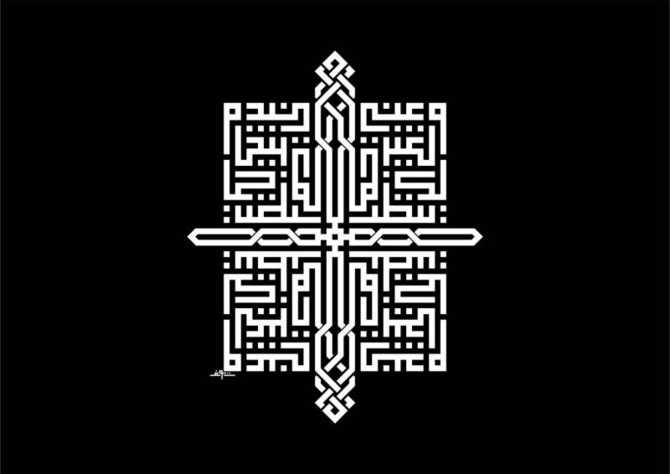

Kufi is still a common script, geometrically constructed with a compass and ruler. It needs very accurate planning, its calligraphers were and still are more like architects of the layout, the lettering and decoration. When calligraphers in training start training in the art of Kufi, the writing will flow quickly and easily, but the training could take years to perfect. In the case of Youssef, architecture has made it easier understanding the elements. Kufi Murabba (square) is very much intertwined with architecture, the lines and measurements are necessary to create balanced lines. Kufi script is known to be a very old form of script, and Kufi Murabba is the latest of its kind and the most simplified. The term “murabba” dictates a display of crafty arrangements in its square like, cubic or checkered nature. It doesn’t flow like written cursive script, but instead it is planned, arranged and constructed to conform into specific shapes.

As far as inspiration goes, the calligrapher gets it from different well-known historic artists such as Ali Toy from Turkey, Abdullah Zuhdi, who is known as a master calligrapher who created the calligraphy script on the Qibla walls of the Prophet’s (peace be upon him) Holy Mosque in Madinah, as well as the great Mustafa Haleem. As for inspiration from contemporary artists, there is Ibrahim Al-Orafi, who is the calligrapher of Makkah’s Holy Mosque. There are also young calligraphers who inspire him such as Mohammed Jamal Al-Rabeia, son of Jamal Rabeia and architect Naser Al-Salem.

Twenty-four-year-old Youssef has displayed his work in the latest Behans Exhibition in Jeddah and was ranked third among the artists displaying their work. He plans to continue his art and is also planning on future collaborations with the Emirati jewelry designer, Bodour Hashem, through applying the Kufi calligraphy in jewelry pieces and diamonds. There is also work in progress in applying the Kufi Murabba in furniture design.

“Sheikh Ali Abu Al-Hasan once said: The writer chooses his script, in the calligrapher’s case however, it is the script that chooses him. This quote really touched me. What relates me to my writings is way more than just a canvas. I see myself practicing Kufi calligraphy now and in the future, since I live with it in my work and studies.”

Be sure to follow Youssef Yahya in his journey of exploring Kufi calligraphy on his Instagram page UCFyahyart.

— [email protected]

Exploring the meticulous art of Kufi Murabba

Exploring the meticulous art of Kufi Murabba

Rubaiya Qatar’s flagship ‘Unruly Waters’ promises compelling curation

DOHA: The ambitious new quadrennial Rubaiya Qatar opens this November across the country and its capital Doha, and its headline exhibition, “Unruly Waters,” promises to be a major intervention in contemporary curation.

The show has four curators: Tom Eccles (executive director, Center for Curatorial Studies and the Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College); Ruba Katrib (chief curator and director of curatorial affairs, MoMA PS1); Mark Rappolt (editor-in-chief of ArtReview and ArtReview Asia); and Shabbir Hussain Mustafa (chief curator, Singapore Art Museum),

It features more than 50 artists and includes over 20 new commissions produced for the project. The show offers both a literal and metaphorical examination of water.

“Water is a kind of foil to talk about something else,” said Eccles at a briefing panel held alongside Art Basel Qatar last week, signaling a show that will use seas, currents and maritime histories to open conversations about trade, migration, ecology and cultural exchange.

The curators’ research was sparked, in part, by a maritime find now in Qatar’s collections: a shipwreck off the coast of Sumatra that yielded tens of thousands of objects and traced routes across the historic Maritime Silk Road.

Eccles said the material “gave us the world to think” beyond conventional regional frames and to reconfigure how an exhibition might map connections from the Gulf eastwards to south and southeast Asia.

The exhibition’s scale is matched by its ambition. “More than half of the show will be commissioned,” said Katrib, underlining the quadrennial’s commitment to new production and artworks conceived in dialogue with Doha’s audiences and sites.

Katrib emphasizes the show’s intergenerational and geographically wide-ranging cast of artists.

And the curators’ intent to foreground histories of trade — cups, pots and the everyday objects that circulated across oceanic networks — alongside more speculative practices addressing climate, migration and contingency.

Rappolt pointed out that “Unruly Waters” “is very much built on the work that our colleagues have done over several years in building infrastructures and networks.”

The curators have drawn on environmental history and scholarship — inviting contributions from historians and hosting academic exchanges — so that the exhibition functions as a platform for knowledge production, and dialogue.

Mustafa spoke about the plural, polyvocal structure of the show. The project maps multiple regions at once. “We have the Arab worlds. We have the Indian ocean worlds. We have Africa, we have Southeast Asia.”

And these zones will sit “alongside each other, not necessarily in agreement, but most certainly in a state of complexity.”