ISLAMABAD: Electronic cries of rage and amusement are ringing across Pakistan’s Twitter community after the government announced on Wednesday its plans to impose a ‘sin tax’ on tobacco products ostensibly to make cigarettes more expensive and reduce the number of youngsters who take to smoking each year.

While sin tax is a commonly used term to mean excise or sales tax on products deemed harmful to society, the translation by Urdu-language media of the word sin as ‘gunnah,’ used to refer to activities that go against the commands of Allah, did not go down too well among Pakistan’s puff-chested, rambunctious Twitter users.

Journalists, cultural critics and members of the ruling Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf party alike took to Twitter to blow off smoke.

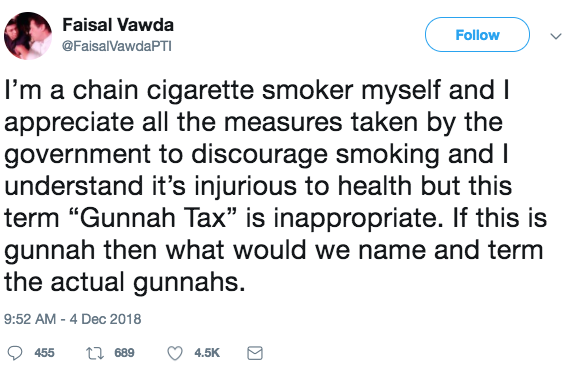

The gunslinging, motorbike-riding parliamentarian Faisal Vawda wouldn’t have any of it.

‘I’m a chain cigarette smoker myself and I appreciate all the measures taken by the government to discourage smoking and I understand it’s injurious to health but this term “Gunnah Tax” is inappropriate,” he tweeted. “If this is gunnah then what would we name and term the actual gunnahs.”

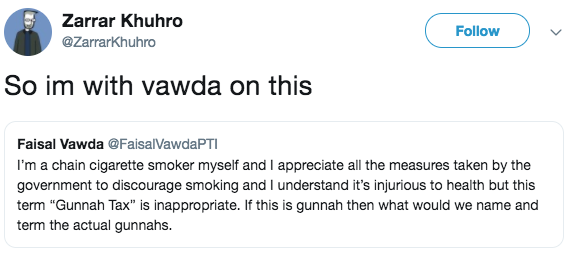

Journalist Zarrar Khuhro, known for his sharp wit and merciless trolling, who is generally never on the same page as Vawda, responded that he was ‘with [Vawda] on this.’

“It is a common term used internationally and is just a literal translation, not a big deal,” Khuhro told Arab News, adding that the outcry was “just another storm in a teacup.”

But Khuhro’s response to Vawda had already unleashed an army of economists (read: people adept at using google search) who proceeded to educate him about what sin tax actually meant and that the use of the word gunnah was merely a translation error. Indeed, the sheer number of people who suddenly emerged as experts on the origins and use of the sin tax since the beginning of time proved beyond a doubt that Pakistanis are capable of google searching a wide variety of topics other than just raunchy content. Ahem.

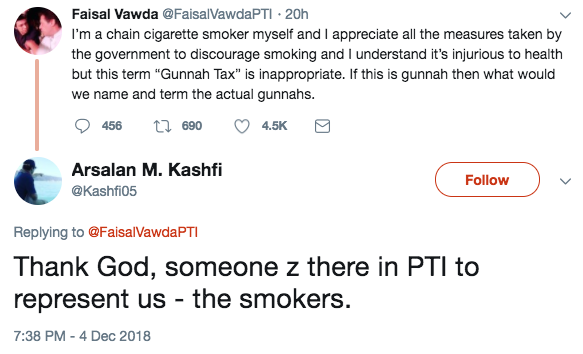

There were also those who welcomed Vawda’s stand.

“Thank God, someone z there in PTI to represent us - the smokers,” Twitter user Arsalan M Kashif said in response to Vawda’s post.

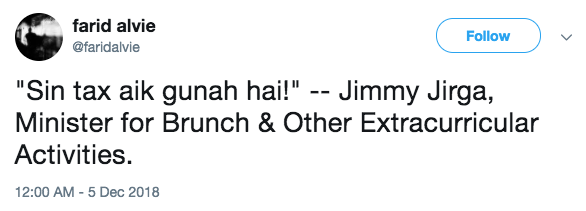

The searingly funny Farid Alvie ascribed the quote “sin tax is a sin” to a make-belief ministry:

"Sin tax aik gunah hai!’ -- Jimmy Jirga, Minister for Brunch & Other Extracurricular Activities,” Alvie posted.

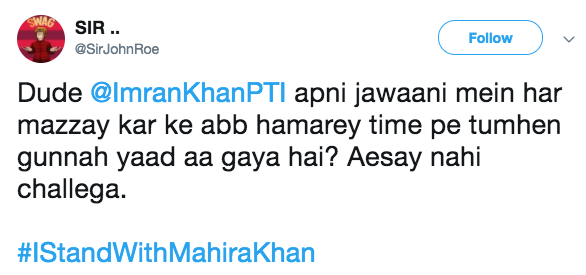

One Twitter user directly addressed the prime minister for raining on his fun:

“Dude @ImranKhanPTI apni jawaani mein har mazzay kar ke abb hamarey time pe tumhen gunnah yaad aa gaya hai? Aesay nahi challega. #IStandWithMahiraKhan.’ (Oh Imran Khan, after having all the fun in your youth, now when it’s our turn you’ve remembered this is a sin? It’s not going to work like this.”

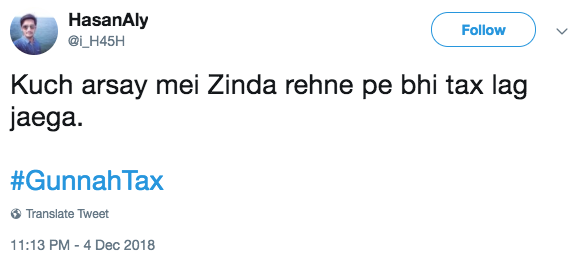

Others took an ever more dramatic approach. Hasan Aly tweeted that soon the government would tax citizens simply for being alive.

Many even revived the #IStandWithMahiraKhan hashtag from last year which was created to express solidarity with Pakistan actress Mahira Khan after she was shamed on social media over leaked photos that showed her smoking in a backless dress with Indian actor Ranbir Kapoor.

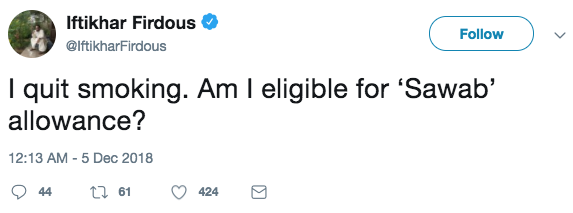

Then there was also those enterprising few who wondered if they could be rewarded for giving up smoking:

“I quit smoking. Am I eligible for ‘Sawab’ (reward) allowance?” Iftikhar Firdous, an editor at Samaa TV, said in a tongue-in-cheek post.

Author, columnist and cultural critic Nadeem Farooq Paracha had his own ideas.

“I sure wish they could have called it something else,” Paracha told Arab News. “Like Indulgence Tax or Fun Tax Or Minor Sin tax or Chota Gunnah (small sin) Tax.”