BAGHDAD/LONDON: With Iraq facing its latest security challenge amid growing protests over unemployment, Iraqis could be forgiven for harking back nostalgically to an era of rising prosperity when the country appeared to be on the cusp of a gilded age.

Sixty years ago, Iraq’s monarchy came to an end with a bloody coup that killed the young King Faisal II. Many Iraqis still believe it was the start of a catastrophic slide downhill.

While it lasted less than four decades, the constitutional monarchy is viewed by many as a golden period in the country’s history. That the king’s execution gave way to a tumultuous republic and, ultimately, the brutal dictatorship of Saddam Hussein, only adds to the sense of nostalgia.

On the anniversary of the July 14 revolution, Iraqis on Saturday reflected on what might have been had the king managed to survive the swirling and explosive political forces tearing through the Middle East at the time.

But some also said the era of the monarchy is too often seen through rose-tinted spectacles, and that the reality was a deeply polarized country divided between the elites and the mostly rural poor.

Sadaih Khalid, 45, a Baghdad businessman, described Brig. Abdul Karim Qassim, the nationalist Iraqi army officer who led the coup, as a “crazy man” who killed the king and other royal family members in “cold blood.”

Qassim “opened the gates of blood and released the killing, torturing and looting, since the dawn of that black July 14 until now,” Khalid told Arab News.

“We wouldn’t have passed through all these tragedies if the royal family was still here.”

The king’s tomb in Baghdad. (AFP)

This sentiment is common in Baghdad, even among those born decades after the dynasty ended. It is not only that the demise of the monarchy was the start of the country’s descent toward dictatorship and years of war, but also that the coup — with no mercy shown toward the royal family — set a precedent for how the country’s most powerful figures would come to deal with political opponents.

That precedent came back to haunt Qassim less than five years later when he, too, was killed during a 1963 coup by the Baath party during Ramadan.

The kingdom of Iraq was founded in 1932 under Faisal I after the fall of the Ottoman empire. Faisal, who was born in Saudi Arabia, was a member of the Hashemite dynasty and fought alongside T.E. Lawrence during World War I.

Faisal ruled for 12 years under a constitutional monarchy imposed by the British until his death from a heart attack, aged 48.

Faisal’s son, King Ghazi, took the throne, but died six years later in a car crash in Baghdad. The title of king fell to Faisal II, who was just 3 years old, and his reign began under the regency of his uncle Crown Prince Abdallah.

Faisal II was educated in Britain at Harrow, along with his cousin, King Hussein of Jordan.

Highly intelligent, and leading a country blessed with a wealth of natural resources, Faisal seemed destined to build on his father and grandfather’s foundations when he took the throne, aged 18, in 1953.

Iraq at the time was prospering. Oil revenues were flowing in and the country was undergoing rapid industrialization.

The kingdom was also gaining prominence on the world stage.

Iraq then was “more democratic and cleaner than today,” Saad Mohsen, a professor of modern history at the University of Baghdad, told AFP recently.

“We were far from the blood and fighting that we have come to know,” he said.

But it was also a country of social polarization. While the wealthy and well-connected enjoyed the good life in a thriving capital, resentment was building among the country’s poor, who were more conservative and receptive to complaints that the monarchy was too compliant to the needs of the West.

“The royal system was not as good as people think,” Abdallah Jawad, 53, told Arab News in Baghdad on Sunday. “People are just tired (of insecurity) and because of this they are willing to go back and live under the royal system.

“They don’t know that most policies adopted by the royal family at that time were sectarian and discriminatory.”

The tide would soon start to turn against the kingdom. Iraq’s close relationship with Britain — a policy Faisal II continued from his grandfather — became the source of increasing hostility that was exacerbated by the Suez crisis in 1956.

On July 13, 1958, when two army brigades were ordered to go to Jordan to help quell a crisis in Lebanon, Qassim, a disaffected officer leading one of the units, saw his chance and sent troops to the Qasr Al Rihab palace. By early the following morning, they had surrounded the palace with tanks and opened fire.

Shortly after 8 a.m., King Faisal II, his uncle the crown prince, and other members of the royal family and their staff were ordered from the rear entrance and killed.

The 23-year-old king was engaged to marry.

Saddam Hussein, who became president in 1979, setting the country on its calamitous course of foreign wars and brutal dictatorship, was fascinated by the young king.

He even restored the royal mausoleum where Faisal II’s marble tomb is located next to his father’s.

Their resting place has survived some of the darkest episodes of the nation’s history. But as Iraq looks to recover from its latest calamity — Daesh’s occupation of large parts of the country — many Iraqis will quietly mourn the 60 years since the monarchy’s downfall.

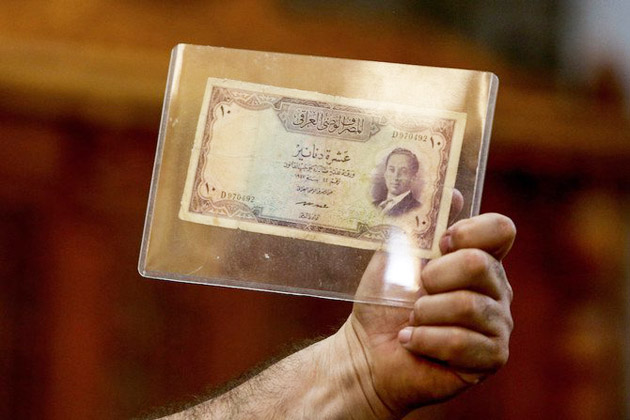

An Iraqi banknote issued in 1947 and bearing the image of King Faisal II. (AFP)

* * *

Born to rule against a backdrop of turmoil

Faisal II was born as the world prepared for a devastating war, lived through an era of Middle East turmoil and growing pan-Arab nationalism, and died in a revolution that also ended Iraq’s monarchy.

He became king of Iraq when he was only 3 years old, in April 1939, after his father, King Ghazi, died in a car crash. Faisal’s lineage crossed borders — his mother, Queen Aliya, was the daughter of Ali bin Hussein, King of the Hijaz and Grand Sharif of Makkah, who had fled to Iraq when he was deposed by Ibn Saud in 1925.

During World War II, when Iraq was allied with Britain and the US, the young Faisal lived with his mother in Berkshire. Later, as a teenager, he was educated at Harrow school, along with the future King Hussein of Jordan, his cousin. The two became close friends, and may have considered merging their kingdoms. Before he became king, Faisal also visited the US in 1952, and met President Harry Truman.

Until Faisal reached the age of 18 in 1953, Iraq was ruled by a regent — his uncle, Abd Al-Ilah. Faisal was an inexperienced boy, plagued by poor health — he suffered from asthma — and his uncle continued to advise him from the sidelines. His advice was that Iraq should continue to have a close relationship with the UK, which resulted in the Baghdad Pact of 1955 — an ill-fated military alliance of Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Turkey and the UK, which the US joined in 1958.

Faisal’s turbulent life came to an end on July 14, 1958, during the revolution that deposed the monarchy. He and other members of his family were rounded up in the palace courtyard in Baghdad, and ordered to face a wall as a machinegun opened fire. The king died on the way to hospital and his body was strung from a lamppost.

As if that were not undignified enough, Faisal attained an immortality of sorts; he was the model for Prince Abdullah of Khemed, a character in “The Adventures of Tintin” by the Belgian comic writer Herge.