BEIRUT: When Fatima Othman, a disabled street beggar, was found dead in an abandoned car in Beirut’s Barbir district on Tuesday night, investigators thought it was simply another tragic death among the city’s poor and homeless.

But internal security forces called to the scene were astonished to find Othman had been carrying bags holding 5 million Lebanese ounds ($3,400) in cash and — even more surprising — a deposit book from a nearby bank that showed she had more than $1 million in savings.

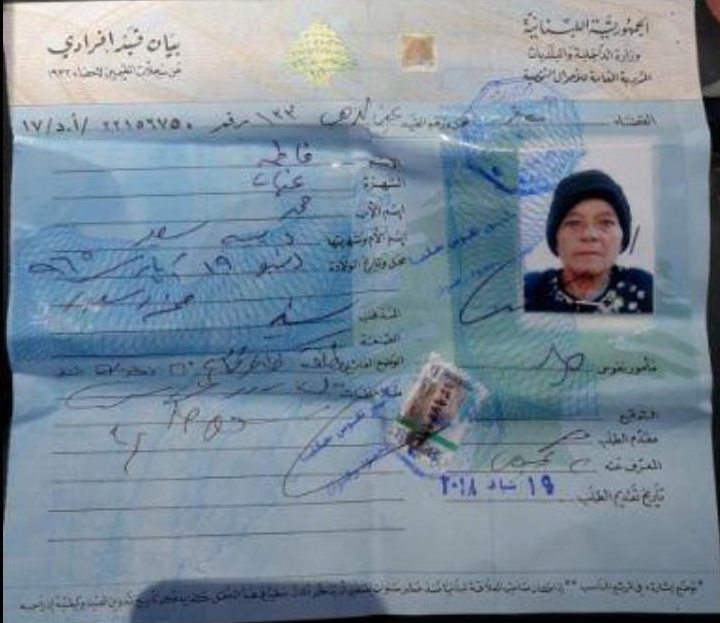

Brig. Gen. Joseph Musallem, director of the Internal Security Forces public relations division, told Arab News that 52-year-old Othman had died of a heart attack.

“Finding the money and the savings book was a big surprise,” he said.

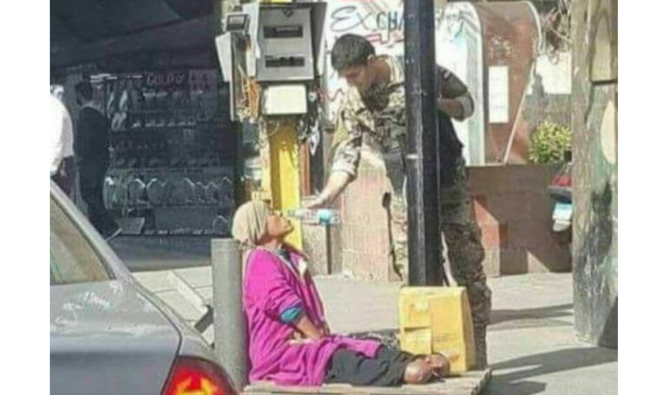

Othman was a well-known figure in the Barbir district. A photograph of the street beggar had won praise with its portrayal of a Lebanese soldier stationed at the nearby Barbir hospital helping her drink because she was unable to use her hands or feet. The soldier was later commended by an army commander for his “compassion and humanity.”

Many on social media mocked begging in Lebanon and derided it as a lucrative profession. But nobody knew Othman as I knew her.

On the pavement where the handicapped beggar used to sit — unable to move her hands due to a birth defect — she had the sympathy of people for decades.

Othman did not talk or beg. She just looked with eyes full of sorrow at passing people.

I used to live in the Ras Al-Nab’a district, and would cross the Barbir district daily on my way to school and, later, to university. Othman used to sit on a newspaper on the pavement near a coffee mill in summer and winter. She would look at me and nod her head, and I would ask how she was. “Alhamdulillah” (“Praise be to God“), she would answer.

The Barbir district was close to the front lines during Lebanon’s civil war and was targeted by artillery, especially during periods of calm when its gold market was crowded with people.

Othman was hit once with shrapnel, but returned to the pavement wearing a bandage. She kept watching us grow up, and we kept watching her grow older.

A week ago, I saw her sitting on the side of the road near the market. Her hair was white and her face full of wrinkles. Her smile had disappeared. I put a coin in her lap as I used to always do, and she held it with her teeth and dropped it inside an open black bag.

After Othman’s death, security forces discovered she was from the town of Ain Al-Zahab in Akkar, northern Lebanon. They contacted her family, and a number of relatives came and took her body to her village. She was buried on Wednesday.

Othman had a family of eight — a mother, two brothers and five sisters.

The family knew nothing about the money, and her savings proved that nobody was exploiting Othman by forcing her to beg.

After daring not tell anyone about her money for fear of being killed, she died without enjoying the benefits of people’s compassion.