DENVER: Places of worship fill many roles in society — and an art installation in the shape of a mosque can invoke polarizing reactions in different lands, as Ajlan Gharem has discovered.

On June 19, the Saudi Arabian artist traveled to Canada to present his life-sized conceptual piece “Paradise Has Many Gates” at the Vancouver Biennale. An interactive installation which renders the unmistakable outline of a mosque in a skeleton cage of cold steel, the work will stand at the city’s Vanier Park — a high-profile public space also home to many museums and music festivals — for two years, during which it will host workshops, talks and performances.

“It’s not just something to show — it’s going to be a new space for ideas, for dialogue, for a new kind of conversation,” Gharem told Arab News.

It is a significant platform for a Saudi artist to exhibit at the noted open-air sculpture and performance festival, which has previously commissioned large-scale public works from Chinese A-lister Ai Weiwei, and this year will welcome Yoko Ono to accept its Distinguished Artist Award.

And it will hopefully offer a happier chapter in the work’s stormy story. “Paradise Has Many Gates” has, in the past, been suddenly pulled from two public appearances, and sparked a violent, viral, social-media debate.

Probing issues of religious orthodoxy, education and Islamophobia, the wall-less structure presents a paradoxical sanctuary. A comfy traditional rug lines the floor, yet there is threatening intent to the glaring fluorescent lights that switch on at sundown. The structure is made from the severe steel fencing normally reserved for cages and border disputes — attracting comparisons to both US military prison compound Guantanamo Bay and the fortifications used to stem the flow of refugees into Europe. The dual imagery perhaps shouts loudest at the five times of the day when the call to prayers emerges, recorded in voices drawn from a variety of Muslim-majority countries.

The installation is one of the first major works from 32-year-old Gharem — younger brother of leading Saudi conceptual artist Abdulnasser Gharem. Inspiration struck when the artist found himself approaching 30, astride a growing generational divide between the Kingdom’s elders and established traditions, and the swelling ranks of youthful voices — with estimates placing around 70 percent of Saudi Arabia’s population under 30 years of age. His website states: “The mosque is a conduit for the symbolic power wielded by all those above the unwitting individual… The mosque is the public square reincarnate but with attendance mandatory, at least socially.”

Aware of the charged nature of his subject, Gharem first erected “Paradise Has Many Gates” in the desert, an hour’s drive outside of Riyadh, conceiving the temporary structure as the subject of a four-minute short film to be presented at galleries overseas. He also shot a series of photographs before disassembling his work the following day without attracting attention. However, when he later shared an image of the piece on social media, it ignited a heated reaction he had not anticipated.

“People started saying ‘This is a mosque made of fences. It’s like a cage,’” the artist recalled. “It was posted on everyone’s account, everywhere — when I opened my timeline all I could see were pictures of the mosque with people saying something bad, or something good. That’s why I was afraid.”

That fear led Gharem to pull the photographs from their planned debut at “Ricochet,” a group show at London’s Asia House, in 2015. He eventually “had the courage” to share the images for the first time at a later exhibition, entitled “In Search of Lost Time,” at London’s Brunei Gallery, SOAS, in early 2016.

The structure itself has proved equally divisive. Later that same year, “Paradise Has Many Gates” was erected in the parking lot of Houston’s Station Museum of Contemporary Art; its first physical appearance since its brief stint in the desert. It was part of another group Saudi showcase entitled “Parallel Kingdom,” and was quickly embraced by the community as everything from a place of worship to a quiet yoga spot. After several weeks, it was all set to be packed up and shipped for exhibition in Aspen, Colorado — but organizers mysteriously pulled the plug at the last minute. Gharem’s mosque stayed in Texas all summer.

And in December, the piece’s projected four-month appearance in Bahrain was cut short after just 24 hours, when people began to use the installation as an actual mosque, and prayed inside.

Such setbacks, Gharem said, only confirmed his belief in the strength of the concept behind “Paradise Has Many Gates.”

“They couldn’t make any reason for why they’re going to take it out — they couldn’t understand… (didn’t) realize what was happening,” he said. “This is good, when you have an idea that brings people together, and you see people you are just afraid of this idea.”

The work’s two-year appearance at Vancouver will undoubtedly raise Gharem’s profile considerably, positioning him at the forefront of the emerging wave of Saudi Arabian artists finding success abroad. However, art is just a part-time calling — Gharem also serves as an elementary school mathematics teacher, a position he is in no hurry to abandon.

“For me the teaching thing is good, it gives me a chance to be among the people, among the society — the revolution is in the kids,” he said. “So, I’m a math teacher by day, and an artist by night.”

Gharem’s first significant solo work was “Mount of Mercy,” an evolving series of heartfelt photographs left by pilgrims visiting the religious site also known as Mount Arafat. Gharem drew from more than 10,000 images he has collected during repeated visits to Makkah over the past six years.

He was encouraged to find his own voice after a decade spent “helping” his famous older brother: Inspired by the lack of institutional support the younger artist encountered, the pair co-founded Gharem Studio, a nourishing, not-for-profit organization offering studio space, training, careers guidance and resources to Riyadh’s growing rank of young artists.

“The scene has really picked up in the last five years,” Gharem said. “Even just three, four years ago, you could only find 10 or 15 artists representing Saudi. Since then everyone has tried to be an artist and gone with the wave. I think now is the time for us, because everything is moving so quickly — at this time we start to see our problems, our issues… Everything is starting to reveal in front of us.

“Now the role of art is to start doing something,” he continued. “It’s the most important time to be an artist.”

Saudi artist Ajlan Gharem gains global recognition for his thought-provoking work

Saudi artist Ajlan Gharem gains global recognition for his thought-provoking work

- Ajlan Gharem traveled to Canada to present his life-sized conceptual piece “Paradise Has Many Gates” at the Vancouver Biennale

- Probing issues of religious orthodoxy, education and Islamophobia, the wall-less structure presents a paradoxical sanctuary

Hollywood Arab Film Festival: Showcasing Arab cinema in Los Angeles

LOS ANGELES: The third annual Hollywood Arab Film Festival began this week, bringing the best of 2024’s Arab cinema to Los Angeles and giving fans a chance to see the films in theaters as well as introducing a new audience to the Arab world’s top talent.

The event, which runs until April 21, was attended by a number of celebrity guests including Egyptian producer and screenwriter Mohamed Hefzy, Tunisian actor Dhaffer L’Abidine, renowned Egyptian star Elham Shahin and Egyptian producer Tarek El-Ganainy.

At the event, Hefty said: “Arab cinema really needs a platform to tell our stories and to show who we are, our identity, our hopes and dreams, our pains, and all the different social topics that are tackled in some of the films that are being presented are maybe more relevant today than ever. So I think it’s a great opportunity to have this dialogue.”

Hefzy’s film “Hajjan” was showing at the event. It is a Saudi Arabia-based film directed by Egyptian filmmaker Abu Bakr Shawky.

“Hajjan is a film about a young boy who got a very special connection to his camel, who has a brother who was a camel jockey and races,” Hefzy said. “And, one day when something really unexpected happens to his brother, and shatters his world, it forces him to step into his brother’s shoes and become a camel jockey, and so starts racing himself.”

The movie is a co-production between the Kingdom’s King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, or Ithra, and Hefzy’s Film Clinic.

“It was a film made in Saudi Arabia with Saudi talents and actors with an Egyptian director, but with the Saudi co-writer and Saudi actors and shot mostly in Saudi Arabia,” Hefzy said. “So I think it’s, it was a great experience, and learned a lot about Saudi Arabia, learned a lot about the culture.”

The festival featured cinema from various Arab countries, presenting films from 16 different nations. Marlin Soliman, strategic planning director of HAFF, highlighted the inclusion of six feature films, ten short films and six student films.

Spanning five days, HAFF offered its audience a vibrant experience, including a red-carpet affair, panel discussions on filmmaking and diversity in Hollywood, and, of course, screenings of high-profile films.

The festival also saw several filmmakers singing the praises of Saudi Arabia’s expanding film industry.

L’Abidine, the writer and director of “To My Son,” said: “I’m thrilled to be back again with my second feature film ‘To My Son,’ a Saudi film… I think there is a great evolution of Saudi cinema that’s been happening in the last few years.”

Art Jameel announces open call for Hayy Jameel Facade Commission

- Antonia Carver, director of Art Jameel, said: “At Art Jameel, we are committed to fostering the role of the arts in public life

JEDDAH: The Hayy Jameel Facade Commission is inviting new and established artists in Saudi Arabia to reimagine the facade of the Hayy Jameel art building in Jeddah.

In its fourth year and third open call process, the commission will select a winning artwork that serves as conversation starter between the complex, the community it serves and the broader public.

Antonia Carver, director of Art Jameel, said: “At Art Jameel, we are committed to fostering the role of the arts in public life.

“Through this annual commission which positions the facade as the first point of contact with the Hayy Jameel community, we are providing a platform that propels mid-career artists forward and challenges them to produce a large-scale, highly imaginative work that remains in-situ, front and center in Jeddah, for around 10 months.”

The commission encourages artists to consider the site-specific nature of the project and the technical requirements of a public work.

Sustainability considerations are also appreciated in managing the carbon footprint of the artwork and its installation.

Eligibility is open to all Saudi and Saudi-based artists and collectives, with at least one member required to be a Saudi citizen or resident if applying as a collective.

The commissioned artists will receive a work fee and a production budget managed by Art Jameel.

The jury, consisting of local and international art professionals, curators, artists and museum directors, will select a single work for production.

Applicants are required to submit a concept statement (200-500 words), up to four sketches and diagrams, and an estimated production schedule through the application portal.

The deadline for the facade submission has been extended to May 1, with the launch scheduled for October. Following the unveiling, there will be a public viewing period from October 2024 to September 2025.

Previous works displayed on the building have showcased the talent of artists such as Nasser Al-Mulhim, Tamara Kalo, Mohammad Al-Faraj and Dr. Zahrah Al-Ghamdi.

Dave Chappelle to perform at Abu Dhabi Comedy Week

DUBAI: US award-winning comedian Dave Chappelle is set to perform in the UAE at the Abu Dhabi Comedy Week on May 23, organizers announced on Friday.

The capital city’s first-ever comedy festival will run from May 18-26 at Yas Island’s Etihad Arena.

Chappelle will join a long list of comedians performing at the event, including Chris Tucker, Aziz Ansari, Tom Segura, Jo Koy, Tommy Tiernan, Kevin Bridges, Andrew Santino, Bobby Lee, Andrew Schulz, Bassem Youssef and Maz Jobrani.

With numerous accolades and awards to his name, including multiple Grammy Awards and Emmy Awards, Chappelle is renowned for his wit and fearless commentary on contemporary issues.

While May 23 will mark Chappelle’s inaugural performance in Abu Dhabi, he has previously captivated audiences with two sold-out shows in Dubai.

Manal AlDowayan on her work for the Venice Biennale

- The acclaimed artist is representing Saudi Arabia at this year’s ‘Olympics of the art world’

DUBAI: The acclaimed Saudi artist Manal AlDowayan is on a roll. Earlier this year, she opened two well-received exhibitions in AlUla, where she is also working on an ambitious land art commission for the upcoming Wadi AlFann cultural destination. And this week, AlDowayan will represent her country at the 60th iteration of the Venice Biennale — dubbed “the Olympics of the art world,” consisting as it does of multiple national pavilions — which runs until Nov. 24. She will be presenting what she describes as “two of my most major works in my career at this point.”

AlDowayan has participated at Venice before. In 2009, she showed her work in an onsite exhibition organized by the Saudi art-focused initiative Edge of Arabia, alongside fellow Saudi artists including Maha Malluh and Ahmed Mater.

“I’ve been going to Venice for about 12 years,” AlDowayan tells Arab News. “The first time I showed there, I knew in my heart that I would be coming back to represent Saudi Arabia; I would do everything in my power to come to this moment and prepare myself. It’s something very important for an artist: to participate in the Venice Biennale.”

It was only last August that she was visited in her UK studio by Dina Amin, the CEO of the Visual Arts Commission, and cultural advisor Abdullah Al-Turki, and told she had been selected to represent the Kingdom in 2024.

“My first thoughts were: ‘There’s no time,’” she says with a laugh. “To come up with a concept, complete the research, execute the concept, build it, and install it, is really complex. But my team, my studios, and I were ready. I already knew what I wanted to present, and within one week I had put together my proposal and it was approved. The artwork is a continuation of my language, my research and my forms that I work with.”

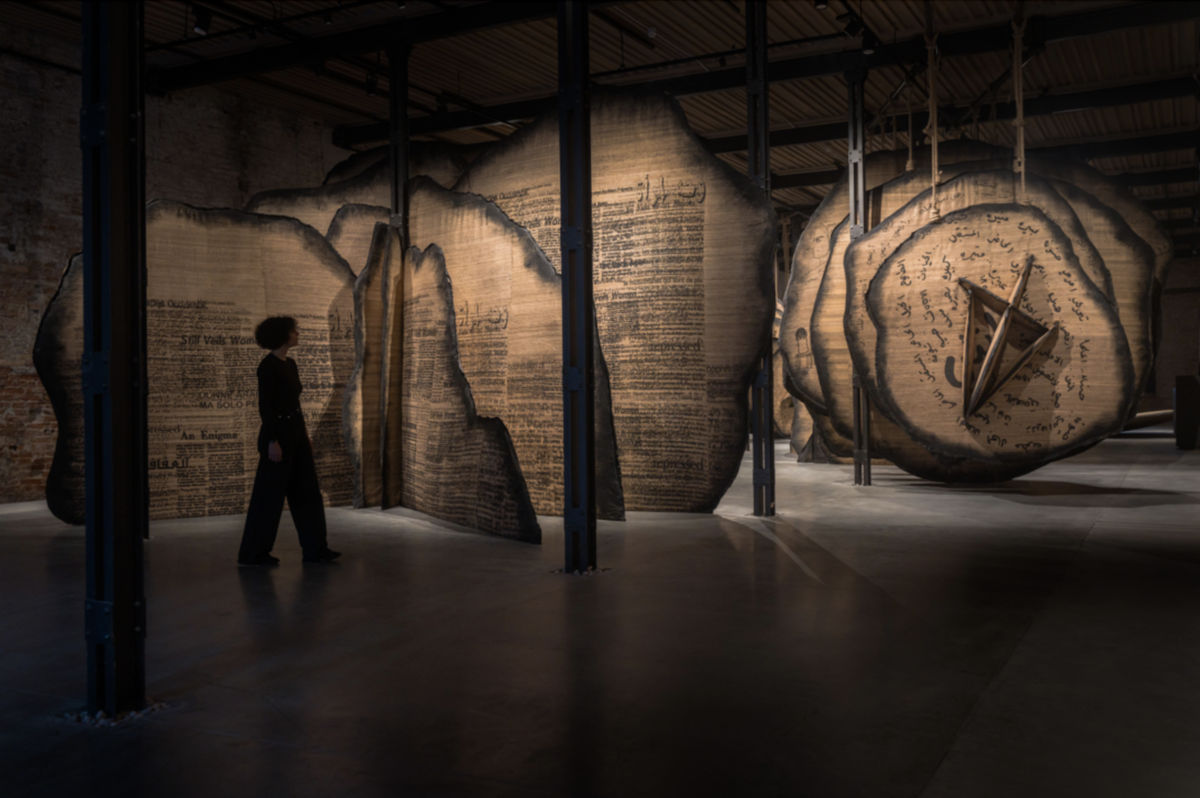

The Saudi pavilion’s theme at Venice this year is “Shifting Sands—A Battle Song.” It is curated by a trio of female art experts, Jessica Cerasi, Maya El-Khalil, and Shadin AlBulaihed. In AlDowayan’s sound-meets-sculpture installation, she brings together much of what she has explored in her practice over the past two decades — community engagement, participatory art, media (mis)representation, and the visibility, or lack of it, of women in Saudi culture. The work is also about the momentous changes taking place in the Kingdom today, and her response to them.

The work comprises two key parts: sound and soft sculptures. Saudi and Arab women’s voices are front and center; AlDowayan allowing them to reclaim their narrative, which she believes has consistently been misrepresented.

“If you’re always told that you’re oppressed, repressed, depressed… you sort of lose the sense of yourself,” she adds. “And this artwork talks about this sort of constant hounding by Western media — and local media — speaking about the Arab woman; her body, her space, the rules of her behavior, and how she should exist in the public space.”

For this section, AlDowayan put out an open call inviting women to take part in workshops. They proved very popular, attended by all ages, professions and backgrounds.

“In Riyadh, within three hours, 350 women registered,” she says. “We had to block the registration link because I don’t know how to control 350 women. I’m just one.” In the sessions, participants reacted to negative press headlines and media clippings, and AlDowayan recorded those reactions.

“I always say that people are trying to define what a Saudi woman is,” explains AlDowayan. “We researched thousands and thousands of articles in my studios, in seven languages, and there were some very dark things written. I showed the women these articles and said, ‘Do you really feel these articles are really speaking your truth?’”

She also asked them to write and/or draw their own stories. Examples included: “Two women equal one man.” “Thanks love, we don’t want to be saved.” And “Surrendering doesn’t look good on us, for we are wars.”

A selection of the written quotes were then read out loud by participants. While reading, they had headphones on, listening to, and harmonizing with, the eerie humming sounds made by sand dunes, which AlDowayan had previously recorded.

“It was beautiful and meditative. You will see women with their eyes closed, their arms stretched out. It was a very spiritual moment,” AlDowayan recalls. The whole ‘performance’ was inspired by ‘Dahha,’ a ritual in which warriors celebrated victory with music and dance.

Inside the pavilion, where the women’s recordings play, stand three soft black-and-brown sculptures, full of folds, shaped like the sand crystals known as desert roses — a recurring motif in AlDowayan’s work.

“The rose is a very weak and delicate (thing),” she says. “But this crystal is born in extreme circumstances. First, it needs to be pouring rain, then there needs to be high temperatures and that’s how it crystalizes. I feel like I’ve adopted this form as a body and I deal with it like skin.”

The folds of the enlarged sculptures are imprinted with “a cacophony of what Western media has written: the veil, repressed, oppressed, women, sexuality… All the words that always float over our heads,” says AlDowayan. They also include some of the women’s positive messages, as well as their drawings.

“While you’re taking this journey you will hear the sound, and sound is sculptural in my opinion: It occupies but you can’t see it,” she says. “I feel the invisibility of sound, and its ‘presence’ is like the Arab woman. She’s strong, she’s there; it’s undeniable. Just because you don’t see her, it doesn’t mean she doesn’t exist.”

As for how visitors will react to her work, AlDowayan hopes to provoke conversations.

“I want questions. I want extreme emotions. They can hate it, they can love it, they can cry. But, I can’t do neutral,” she says. “Neutral means I did not succeed. If they have questions, then I’ve succeeded. If they talk about it after one day, I’ve succeeded.”

US Kuwaiti artist Latifa Alajlan — ‘I used to compare myself to other artists’

- The third in this year’s series focusing on contemporary Arab-American artists in honor of Arab-American Heritage Month

DUBAI: Kuwaiti artist Latifa Alajlan moved to America in 2016 to study art at Grossmont College in San Diego, followed by a Master of Fine Arts program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where alumni include major American artists Georgia O’Keeffe, Joan Mitchell and Grant Wood.

Now, Alajlan is based in New York, where she is represented by Franklin Parrasch Gallery. “New York is the Makkah of the art world,” she tells Arab News. “You have so many galleries and institutions — that’s what I do every Friday. It’s very meditative for me and I enjoy walking around the city.”

But she is also aware of the competition in such an established artistic environment. “In New York, when you’re a young artist what’s dangerous about it is that you compare yourself to other artists,” she says. “I used to do that a lot and I had to take a step back and realize it was unhealthy. Everyone has their own journey.”

Hers began in Kuwait, where her parents, especially her strict father, would “force” Alajlan and her siblings to visit museums and write essays on artworks. “I just didn’t understand. People were enjoying their summer, and we were going to museums,” she says. “That was boring.”

Now, however, Alajlan can look back on her childhood and understand her parents’ intentions. “That’s what I appreciate: the fact that they kept pushing me,” she says.

As for her creative practice, Alajlan has experimented with ceramics, glass-blowing, blacksmithing and sculpting. But such labor-intensive mediums weren’t for her. “I almost lost my fingers,” she says. “It’s intense. . . I’ve realized painting is my thing.”

Through her abstract work, Alajlan addresses political, cultural and architectural attributes of her homeland. But she finds inspiration everywhere, she says — from her friends to conversations with strangers. There is an element of mystery to her canvases; she might hide certain parts of her composition with splodges of paint, filling them with gentle gestural strokes and motifs from mosques.

“To me, painting is very therapeutic,” she says. “It’s my way of praying.”