The term “fake news” was chosen as the phrase of the year in 2017 by Collins Dictionary. False stories that appear to be true have helped to undermine society’s trust in news reporting.

On Jan. 10, President Emmanuel Macron announced that France would be the first country to shut down alleged fake news websites and social media accounts if they were suspected of interfering with democratic elections.

Dishonest outlets should not be allowed to influence public opinion. But people need to be trained to become critical thinkers. A Stanford University study tested 7,800 students for 18 months and discovered that young people are unable to recognize high-quality news from lies.

Lies have become weapons and they are difficult to detect. “Misinformation is devilishly entwined on the Internet with real information, making the two difficult to separate,” says Daniel Levitin, a neuroscientist, cognitive psychologist and bestselling author.

Misinformation passes from one person to another through a range of social media and spreads around the world. However, governments and powerful individuals have used disinformation to serve their own interests for millennia.

This book shows us, on one hand, how to detect problems with data we encounter on the Internet and, on the other, gives us the tools to think critically, evaluate facts and reach evidence-based conclusions. Students are reading increasingly less. Consequently, “children are not developing good learning habits, they’re not interested in bettering themselves, and they are not intellectually engaged,” writes Levitin.

Most of what we know was either told to us or we read about it. In other words we rely on people with expertise. We should analyze the claims we encounter the same way we analyze statistics and graphs. This is taught in law and journalism schools, and sometimes in business schools and graduate science programs, but rarely to those who need it most.

To reach the truth can be quite an ordeal and the human brain often makes decisions based on emotional considerations. “Even the smartest of us can be fooled. Steve Jobs delayed treatment for his pancreatic cancer while he followed the advice (given in books and websites) that a change in diet could provide a cure. By the time he realized the diet wasn’t working the cancer had progressed too far to be treated,” writes Levitin.

Another important factor is to be able to evaluate the reputation and trustworthiness of experts. So many financial authorities make the wrong predictions, while novices or amateurs turn out to be right.

Some sources are more reliable than others: peer-reviewed articles are more accurate than books, and books by major publishers are more reputable than self-published works. Award-winning newspapers such as The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal gained their reputations by striving to be constantly truthful in their news coverage. These outlets maintain their standards on their websites. The same cannot be said of some other websites, which fail to live up to the same standards.

Another form of misrepresenting the truth is “counterknowledge”, a term coined by Damian Thompson, a British journalist, referring to misinformation packaged to resemble real facts. Examples are claims that the Moon landings and 9/11 terror attacks in the United States never took place. Merely asking the question “What if it is true” helps the fake news to spread.

In the final section of the book, Levitin tackles scientific thinking and “that includes seeing how, with our imperfect human brains, even the most rigorous thinkers can fool themselves”.

Some researchers make up data. They often get away with it because their peers are not on their guard. A case of fraud was discovered in 2015 when Dong-Pyou Han, a former biomedical scientist at Iowa State University, was found guilty of fabricating and falsifying data about a potential vaccine. He lost his job at the university and was sentenced to almost five years in prison.

The idea that the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine may cause autism was propagated by Andrew Wakefield in an article with falsified data that has now been retracted and yet, even now, millions of people continue to believe the link.

The Internet is a powerful democratizing force that allows everyone to express their opinion and enjoy instant access to the world’s information. But critical thinking and updating our knowledge are needed as new information come in.

“We’re far better off knowing a moderate number of things with certainty than many things that might not be so. True knowledge simplifies our lives, helping us to make choices that increase our happiness and save time,” says Levitin.

“Weaponized Lies” warns us about the logical fallacies, the insidious lies and fake news found on the Internet. It also gives us a set of intellectual tools to uncover inaccurate data, deceptive information, fallacious reports and, finally, differentiate between the real, the unreal and even the surreal.

Book Review: Re-thinking strategy in the fight against fake news

Book Review: Re-thinking strategy in the fight against fake news

What We Are Reading Today: The Empire of Climate

Author: David N. Livingstone

Scientists, journalists, and politicians increasingly tell us that human impacts on climate constitute the single greatest threat facing our planet and may even bring about the extinction of our species. Yet behind these anxieties lies an older, much deeper fear about the power that climate exerts over us.

“The Empire of Climate” traces the history of this idea and its pervasive influence over how we interpret world events and make sense of the human condition, from the rise and fall of ancient civilizations to the afflictions of the modern psyche.

Taking readers from the time of Hippocrates to the unfolding crisis of global warming today, David Livingstone reveals how climate has been critically implicated in the politics of imperial control and race relations; been used to explain industrial development, market performance, and economic breakdown; and served as a bellwether for national character and cultural

collapse.

REVIEW: Amazon Prime Video’s ‘Fallout’ takes gaming adaptations to next level

LONDON: Don’t say it too loud, but we might, finally, have reached the point when good TV adaptations of hit videogames become the norm, rather than the exception. Hot on the heels of “The Last of Us” and “The Witcher” comes “Fallout,” an eight-part series based on the post-apocalyptic world explored in the series of famed Bethesda games.

In an alternate future, with the world devastated by a global nuclear war, a community of wealthy individuals retreats to a series of underground vaults to ride out the fallout. Some 200 years later, wide-eyed vault dweller Lucy (Ella Purnell) is forced to leave the safety of her underground home when her father is kidnapped by raiders from the surface, kickstarting a journey that will not only make her confront the horrors of the unlawful society above, but also sees her meet a revolving door of eccentric (yet equally horrifying) characters along the way. Among these are Maximus (Aaron Moten), a squire in the militaristic Brotherhood of Steel, and The Ghoul (Walton Goggins), a terrifyingly mutated former actor now forging his way as a bounty hunter.

The key to the success of “Fallout” is that your enjoyment of the show is not dependent on whether or not the previous paragraph made any sense to you whatsoever. Rather, creators Graham Wagner and Geneva Robertson-Dworet, along with developers (and executive producers) Christopher Nolan and Lisa Joy have taken the wise decision to create a world wherein knowledge of the wider “Fallout” universe is a bonus, but not a prerequisite. So even if this is your first introduction to the world of Pip-Boys, gulpers and Vaulters, you won’t be penalized, and you certainly won’t feel like you’re missing out.

The world of “Fallout” is a gloriously gritty, bloody and savage one, but it’s also one of razor-sharp humor and fiendish satire — not least thanks to Goggins’ phenomenal turn as The Ghoul. Acerbic and frighteningly violent, The Ghoul is the very embodiment of the savage, unforgiving wasteland, and Goggins has a blast with perhaps the role of his career to date. Lucy is the polar opposite, and Purnell is equally as great as the naïve-yet-capable young woman entirely unprepared for the muck and murder she emerges into. Throw the two together with a razor-sharp, witty script and top-drawer production values and you have a show that’s about as much fun as you can have without a controller of your own.

What We Are Reading Today: Basic Equality

Author: Paul Sagar

What makes human beings one another’s equals? That we are “basic equals” has become a bedrock assumption in Western moral and political philosophy.

And yet establishing why we ought to believe this claim has proved fiendishly difficult, floundering in the face of the many inequalities that characterise the human condition.

In this provocative work, Paul Sagar offers a novel approach to explaining and justifying basic equality. Rather than attempting to find an independent foundation for basic equality, he argues, we should instead come to see our commitment to this idea as the result of the practice of treating others as equals.

Moreover, he continues, it is not enough to grapple with the problem through philosophy alone — by just thinking very hard, in our armchairs; we must draw insights from history and psychology as well.

What We Are Reading Today: ‘Lord of the Flies’

- The novel explores themes of human nature, civilization, power and the inherent darkness within individuals

Author: William Golding

“Lord of the Flies” is a coming of age novel by British novelist William Golding. First published in 1954, the title has since become a classic of modern literature.

It tells the story of a group of British boys who find themselves stranded on an uninhabited island after their plane crashes during a wartime evacuation.

The novel explores themes of human nature, civilization, power and the inherent darkness within individuals. As the boys struggle to survive and establish order on the island, their society gradually descends into chaos and savagery.

The title refers to a severed pig’s head, symbolizing the evil and primitive instincts that take hold of the boys.

The main characters in the novel include Ralph, a charismatic and responsible boy who tries to maintain order and establish a signal fire to attract rescuers; Jack, a power-hungry and savage boy who becomes the leader of a group of hunters; Piggy, an intelligent but socially marginalized boy who serves as Ralph’s adviser; and Simon, a quiet and introspective boy who experiences a deep connection with nature.

As the story progresses, the boys’ civilization erodes, and they succumb to their primal instincts, engaging in violence and tribal warfare.

“Lord of the Flies” explores the destructive potential of unchecked power, the loss of innocence, and the conflict between civilization and savagery.

The novel has always been subject to various interpretations and perspectives by different readers and scholars. Much of it has been analyzed through the lens of allegorical human nature, political and social commentary, and even Freudian psychology.

“Lord of the Flies” has left a lasting impact on literature and popular culture through its exploration of universal themes, and its enduring relevance in contemporary society.

Its portrayal of the human condition and the fragility of civilization continues to resonate with readers, making it a classic that is worthy of being read again.

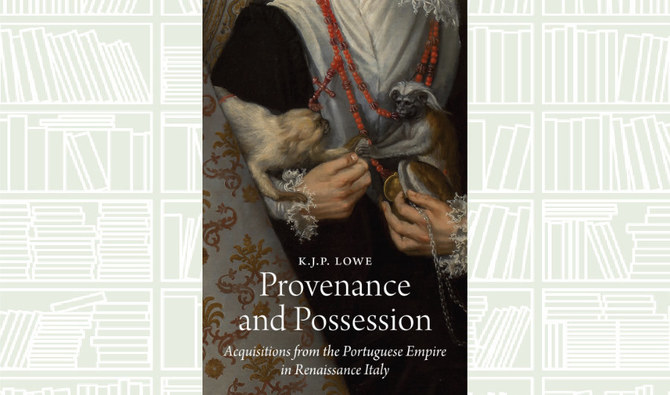

What We Are Reading Today: ‘Provenance and Possession’ by K. J. P. Lowe

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Renaissance Italy received a bounty of “goods” from Portuguese trading voyages—fruits of empire that included luxury goods, exotic animals and even enslaved people.

Many historians hold that this imperial “opening up” of the world transformed the way Europeans understood the global.

In this book, K.J.P. Lowe challenges such an assumption, showing that Italians of this era cared more about the possession than the provenance of their newly acquired global goods.